Pain sells. We love to watch the descent into hell of the mentally anguished and the chronically addicted. We just adore our voyeuristic glimpses into childhoods scarred by cruelty and abuse. And of course, we hope to be redeemed by an emerging message of spiritual survival against the odds.

Pain sells. We love to watch the descent into hell of the mentally anguished and the chronically addicted. We just adore our voyeuristic glimpses into childhoods scarred by cruelty and abuse. And of course, we hope to be redeemed by an emerging message of spiritual survival against the odds.At least that's what the publishers on both sides of the Atlantic appear to be banking on in 2006.

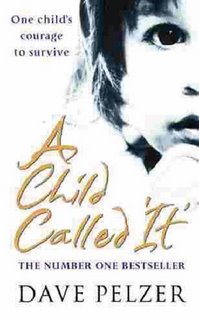

Michael Prodger in the Telegraph blames Dave Pelzer's abuse memoir A Child Called 'It' for starting the trend and notes that:

... the flood of misery he unleashed still shows no sign of abating. ... alumni of the school of Pelzer are everywhere. ... Whether your ailment is physical or psychological, there will be a memoir to suit. You're no oil painting? Try Ugly, Constance Briscoe's account of how her mother hated her looks and everything else about her (the author, incidentally, looks rather fetching in her jacket photograph). Behavioural difficulties? Joe by Michael Blastland recounts the pain (and occasional pleasures) of living with an autistic son. Eating disorder? The Invisible Girl is Peter Barham's memoir of his dead anorexic daughter. Disability? White on Black by Ruben Gallego details a Russian man with cerebral palsy. Grim home life? Dragonslippers is Rosalind Penfold's diary of a decade in which she endured physical, mental and sexual abuse as a wife. (Or, failing that, there's also A Secret Madness in which Elaine Bass recalls marriage to a man with compulsive obsessive disorder.) Drugs? Out of Time by James Fountain tells how a lemonade and LSD cocktail sent him into a psychiatric unit. That's just January's crop - and not all of it.Tim Adams in the Observer identifies the same publishing trend and believes that:

These books invariably come garnished with a carefully defined set of adjectives that can be well merited: the stories they tell are 'inspiring', 'profound', 'touching', their authors are always 'brave' and the books themselves are never less than 'remarkable'. The ordeals the authors have endured are undoubtedly harrowing in the extreme, their reasons for sharing their experiences are cathartic, possibly altruistic and totally understandable. The books world might indeed be a blander place without this grist. But where most non-fiction offers the reader a range of possible responses, these books offer, or rather demand, only one - empathy. With poignancy comes impoverishment.

Misery is set to be the new celebrity.Hmmm ... I remember when the Brits would actually be more inclined to find humour instead of pathos in such accounts. (Anyone else remember the Born in a Shoebox sketch from The Secret Policeman's Ball?)

... It is tempting - though profoundly odd, given what is on the news - to see these narratives as our war stories, vicarious triumphs over outrageous adversity, except that these wars are nearly all private ones, and the battleground rarely extends beyond the author's head. Since Pelzer sold many million copies of his books, there has inevitably been a kind of arms race of his kind of extreme confession. Some of these horrific childhoods have been imported from America - including that of Pelzer's brother Richard - but the British have been quick to embrace the mood. Strange to think now that despite several years on the top of the American bestseller list, no publisher here bought Dave Pelzer initially, thinking his mix of abasement and aggrandisement would not wash on this side of the Atlantic: how wrong they were.

But there's misery and there's misery, I suppose. What makes a book palatable in the end is surely great writing. Frank McCourt's Angela's Ashes is one of the strongest memoirs I've read and rises way above maudling self-pity.

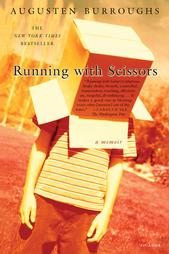

And one book about an abusive childhood I must read is Augusten Burrough's Running with Scissors: his account of a childhood with an alcholic father and manic-depressive poet mother who eventually gave him away to a deranged psychiatrist in whose household he was fed drugs and sexually abused.

Incidentally, there's an interesting little aside in Robert Chalmers interview of Burroughs which could happily be tossed into the Frey fray(!):

He (Burroughs) has never called his work autobiography, but memoir, a term whose standard definition ... doesn't explicitly demand rigorous adherence to fact.

4 comments:

Misery is why newspapers report crime and accidents.. people like to think other lives are worse than theirs. Is it legal to say "many million copies" in Britain ? :)

I've not read your entire post yet because it's truly long. ^_^" Anyway, I would just like to say that "A Child called It" was truly a depressing book I've ever read. :P The way he writes how his mother abused him....it's truly sickening. And there are some that say he exagerated and that it is untrue, but who's to know, right?

I have got quite a few of this kind of books on my shelves. I started with women accounts of their miserable life. Then, I realised that men were suddenly confessing abuses other than political segregation or torture (that make them look like heroes). They were admitting having had to endure pain and traumas at the hands, or from the hands of their most trusted people: be it sexual, emotional, physical, spiritual, you name it. I can't say that pleases me; I am glad that men come forward as having been very vulnerable and not feeling ashamed about that. Now, are they doing it solely for the money? The same question must be asked about women. A child is a child is a child........

anon - yes, i'm sure that's part of the attraction

cheeky monkey - yes, sorry for length of post - i do get carried away and end up wanting to put in far more than i should - the long and short of it is though that if you want more misery books, there will be plenty on the market in 20006

i think waht you say is true, anna

Post a Comment